As our next contributor, we are honoured to introduce Prof. Luciano Mulè Stagno to the Green Deal Malta platform. In his article, he discusses Solar Energy relating to Malta’s National Renewable Energy Plan and ‘MEDSolar’s new solar panel prototype. Prof. Mulè Stagno explains why Malta decided to base their renewable energy plan on Solar Energy. This was due to a price drop, resulting from overcapacity in the market, and Chinese companies entering the market. He then goes on to explain how ‘MEDSolar’ has developed a prototype for an aesthetically pleasing and more efficient solar panel. Find out more by reading the below contribution!

Malta started a serious drive toward renewable energy in around 2008-2009. The aim was to generate 10% of the country’s total energy from renewables by 2020, and the original plan was to get the lion’s share of green energy from an offshore wind-farm which would have been built on a reef outside of Mellieha, known as ‘Sikka l-Bajda’.

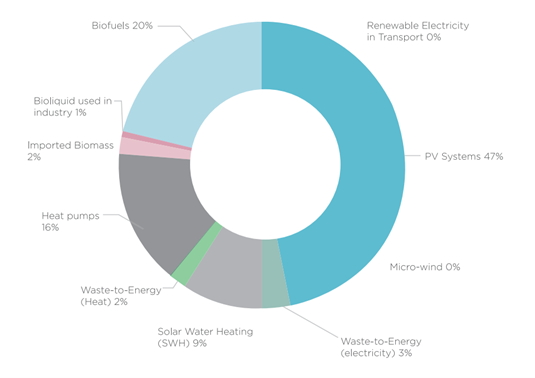

This was a good plan, given that at the time it was significantly cheaper to generate electricity from wind than from photovoltaic (PV) solar energy. However, something changed in around 2011 and the price of solar systems started falling rapidly. By 2013, the price of a PV system fell by half its original value. This fact, coupled with possible environmental issues with the ‘Sikka l-Bajda’ site, lead the Maltese Government to re-think the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP). An updated Plan published by the Government in 2014 focused much more on solar energy, which was planned to produce almost half the renewable energy by 2020 (as seen in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Contribution by technology as a percentage share of the overall target (NREAP 2015-2020).

The reason PV prices dropped so precipitously in those 2-3 years was a confluence of two major factors:

- Until the mid-2000s, when solar was just starting out, polysilicon, the raw material used for solar cells was mostly used for the micro-electronic industry. Solar was just a tiny share of global consumption. When the solar industry started accelerating, the share of polysilicon needed for the solar industry started to increase rapidly, causing a worldwide shortage. This in turn resulted in a rapid increase in prices, and by the late 2000s, existing producers were planning to increase their production capacities and new players were planning on entering this lucrative market. By about 2012, a lot of that new capacity had come online, resulting in overcapacity and a drop in prices.

- The second factor was the entry of Chinese companies into (and eventual dominance of) the market in a big way.

As a result, solar energy became among the cheapest forms of renewable energy, resulting in a boom in worldwide installations.

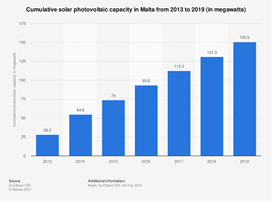

Since then, photovoltaic panels have become a common sight on Maltese roofs. The total installed capacity currently stands at around 180-190MWp (as seen in Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: PV installed capacity by year in Malta.

Looking at it from another angle, there are around 600,000 solar panels installed in Malta, that is, more solar panels than people. And there’s plenty of room for more.

But have you ever wondered why solar panels look the way they do? Most solar panels all look similar and are about 1m wide and 1.5-1.8m tall, with an aluminium frame and front tempered glass covering an array of solar cells (as seen in Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: A photo of a typical solar panel (taken from Wikimedia commons).

This “standard” format developed with the industry and hasn’t changed much over the year. It provides a robust, rigid panel and an ideal shape and size for workers to install on slanted roofs and in large solar farms (as seen in Figure 4 below). The glass exterior, aluminium frame and backside sheet protect the solar cells (which are in fact quite fragile) from the elements and from breakage.

Figure 4: Solar panels installed on a slanted roof.

When it comes to flat Mediterranean roofs however, this fit is not as suitable, especially when it comes to smaller roofs, and often creates an eyesore (see Figure 5 below).

Figure 5: Solar panels installed on a Maltese roof (Taken from Times of Malta website).

The ‘MEDSolar’ project, which has received funding through the Malta Council for Science and Technology’s (MCST) FUSION program, is developing a system from the bottom up, keeping Mediterranean flat roofs in mind. The solution would not only provide the same benefit as traditional systems in terms of energy generation, but will be easier to install, have energy saving benefits and be more aesthetically pleasing for our urban environment.

This is similar to what others have done in Northern climates where they made solar shingles (solar roof tiles), i.e. integrating PV panels into house design.[1] In Malta and other similar countries where flat roofs are prevalent, this solution is of course not practical. The ‘MEDSolar’ solution was designed with our reality in mind. We are currently performing proof of concept tests of the first prototypes and should have a final prototype later this year, whilst a patent for the design is also being filed.

[1] https://solarmagazine.com/solar-roofs/solar-shingles/.

Contributor(s)

Prof. Luciano Mule'Stagno

Is the Director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy and Group Leader of the Solar Research Lab at the University of Malta. He holds a Ph.D in Physics from the Missouri University of Science and Technology. He returned to his native Malta in 2007 from the US where, after his PhD studies, he spent 12 years working with MEMC Electronic Materials. His last post there was that of Director of Worldwide Labs with responsibility for labs in Asia, Europe and the US. His major expertise is in the characterization, engineering and synthesis of semiconductor and solar materials He has published extensively and holds 10 patents on semiconductor/solar materials. His current research interests are primarily in the areas of photovoltaics systems and materials including offshore solar. Luciano has a passion for heritage and environmental issues. In fact his first post in Malta was that of CEO of Heritage Malta (2007-2009) and he is an executive committee member of Din L-Art Helwa (The National Trust of Malta). He is also Chairman of the COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) scientific committee, President of the University of Malta Academic Staff Association and has served on the boards of several local companies.